This systematic review by Dehghanzadeh et al. aimed to synthesis research findings regarding the use of gamification in K-12 education. Just like the review by Lorenzo-Lledo et al. (2023), these authors use the PRISMA framework, but employed a narrative analysis approach as opposed to a thematic analysis approach. In their analysis, gamification was found to be potentially effective for “promoting cognitive, affective and behavioural learning outcomes in K-12 education, primarily by stimulating students’ motivation and raising their level of engagement” (Dehghanzadeh et al., 2024, p. 61), as most reviewed articles report a “positive effect… on various cognitive, affective and behavioural learning outcomes” (Dehghanzadeh et al., 2024, p. 60). Although my age range of interest is more niche than this (3-8yo), the review still provides valuable insights, especially from the studies that focus on my age range and those close to it. As my area of education is private music, which hinges completely on a student’s motivation to practice and persevere, the idea of stimulating a students’ motivation and raising their level of engagement is especially relevant to me.

The authors found that articles associated positive findings to a student’s internal processes when engaging in a game environment (eg, motivation, feeling involved, competition), stating that such feelings, when applied to learning, will increase student engagement. I find myself wondering about the connections between this and Csikszentmihalyi’s idea of Flow. In terms of motivation, both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation can be tapped into using gamification, with external rewards (points and badges) targeting extrinsic motivation, and elements that affect learner’s needs for competence and autonomy (Eg, challenges, collaboration, curiosity) targeting intrinsic motivation. It is worth noting that ‘competence’ and ‘autonomy’ are two out of three basic psychological needs of Self-Determination Theory, which is an interesting connection. I have also been “warned” by existing literature that gamification will never be the answer to motivation, as it takes something much deeper to affect a learner intrinsically. So, it is comforting and also surprising to see the authors connecting certain game elements to intrinsic motivation.

While the history of gamification research as found by the the authors promote a generally positive outlook on the topic, it is not without it’s limitations. Studies in their systematic review also revealed both neutral and unfavourable learning outcomes due to gamification. The authors attribute this to reasons that, to me, fall under 2 main categories:

- Gamification implementation must be adaptive. Dehghanzadeh et al. (2024) finds that “the successful implementation of gamification in educational contexts requires an adaptive (and not one-fits-all) approach” (p. 56). For example, the review’s findings showed that female students and low-achiever students were less enticed by competition (eg, leaderboards), whereas older users were more influenced this due to social comparison. This consideration is not just regarding users of a gamified learning platform, but also regarding intended learning outcomes.

- Gamification will not work on its own. The authors place a strong emphasis on the idea of “instructional supports” within gamification in order for it to be effective in improving student engagement and learning. They state that “without instructional support in gamified learning environments, students are more likely to learn to play the game (ie, in-game performance) rather than learn domain-specific knowledge and skills” (Dehghanzadeh et al., 2024, p. 58). Instructional supports included feedback within the gamified platform, advice to the student within the platform, and interactivity between student and teacher. However, the authors did not find a specific instructional support that can be used exclusively across the board, which mirrors the previous section: gamification implementation must be adaptive.

These are two strong statements that I intend to take with my into my research.

Just like many other systematic reviews, this one also compiles a list of game elements. The authors found points to appear the most across their list of studies, likely due to it’s pull on extrinsic motivation. Let’s be honest with ourselves, who isn’t at least a little enticed by points? The second most frequently utilised game element was level, is likely attributed to the fact that levels are the way that a gamer’s progress is visualised to them. This, especially, would allow “for students to be the active protagonist of their own learning” (Lorenzo-Lledó et al., p. 870). The third most utilised game element is leaderboard, tapping into the social competition aspect and provides an opportunity for learners to participate with each other. Interestingly, the authors made it a point to mention that no trend has found to show which game elements are more effective in achieving learning outcomes, which again confirms that gamification implementation must be adaptive.

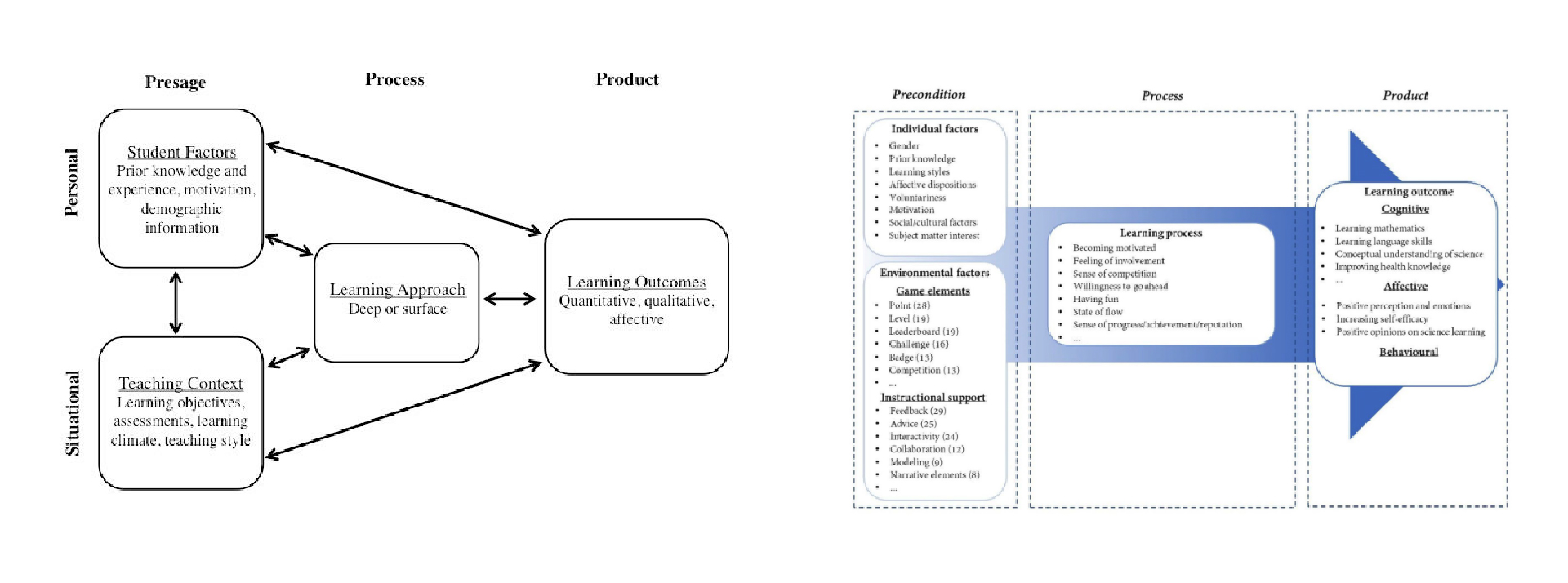

Additionally, the authors propose an evidence-informed framework, in line with Biggs’ (2003) 3P framework, in order to guide teachers and scholars as they develop gamified learning environments. This adapted framework was also used to conduct their systematic review and analysis.

In my opinion, it is a well substantiated framework that carefully considers the theory of the original and interlaces the concept of gamification. This is, however, the first framework that I have seen modified for gamification, so I may have a more informed opinion further down the track. Regardless, I think it’s important to adapt existing pedagogically sound frameworks for education as it gives us a strong basis.

It also provides gaps and implications for future research on the topic of K-12 gamification. It would appear that there is a lack of empirical studies that:

- focus on constructively aligned gamified courses

- examine the effects of different gamification elements on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in different educational contexts

- use data from gamified learning environments (eg, scores, assessments, time spent engaged in the app)

- consider the sustainability of gamification (authors suggest longitudinal studies)

With the exception of the final gap, I believe the first three are all gaps that I can potentially fill (or at least a little bit) with my proposed project. For instance, with the knowledge now that different gamification elements potentially targeting intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, I can angle my research to contributing findings to that area but in the context of private music education, which I believe to be a field that requires a lot of motivation on the students’ part. Additionally, as my research does surround a digital gamified learning platform, I can also use data generated from said platform to inform my findings.

References

- Biggs, J. (2003). Constructing learning by aligning teaching: Constructive alignment. In Teaching for quality learning at university (2nd ed., pp. 11–33). The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Dehghanzadeh, H., Farrokhnia, M., Dehghanzadeh, H., Taghipour, K., & Noroozi, O. (2024). Using gamification to support learning in K-12 education: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(1), 34–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13335

- Lorenzo-Lledó, A., Vázquez, E. P., Cabrera, E. A., & Lledó, G. L. (2023). Application of gamification in Early Childhood Education and Primary Education: Thematic analysis. Retos, 50, 858–875. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v50.97366